Hello, aspiring ethical hackers. This blogpost is a complete guide to Cewl wordlist generator. Cewl stands for Custom Word List generation. It is written in ruby language. Unlike crunch that takes input from us to generate a wordlist, this tool spiders a given website to the depth specified by us and then creates a dictionary or wordlist from it. This wordlist can then be used for password cracking with tools the Brutus, Hydra, Medusa and John The Ripper. It was designed by Robin Wood based on a discussion on PaulDotCom about creating wordlists by spidering a target website.

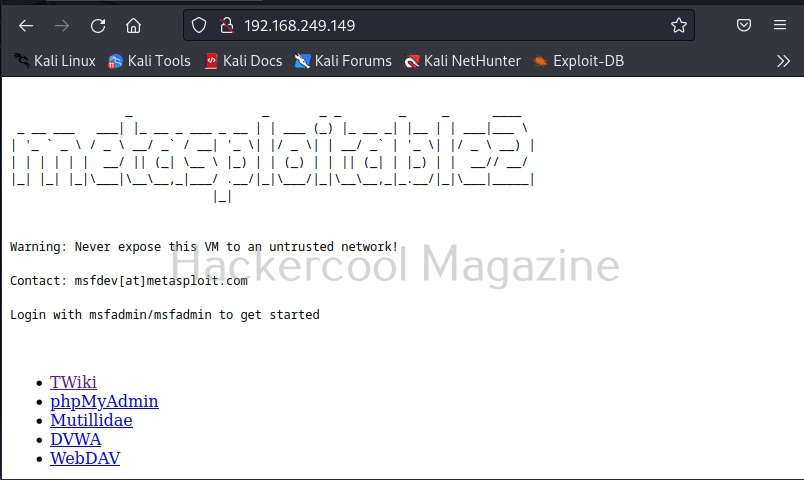

Cewl can be downloaded from here. Kali Linux has cewl installed by default and for this tutorial we are using the same. Metasploitable 2will be used as target since it has lot of applications installed that can be used for testing it.

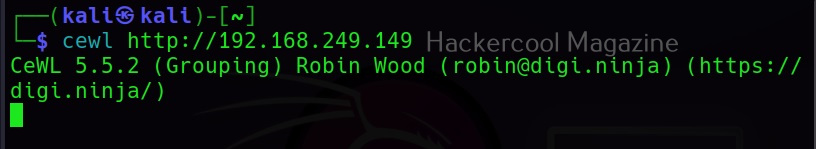

To use cewl, all we have to do is simply supply the URL you want to spider for as shown below.

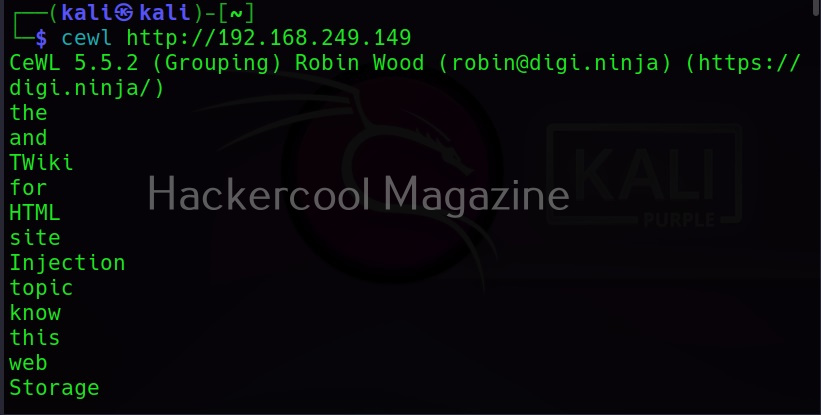

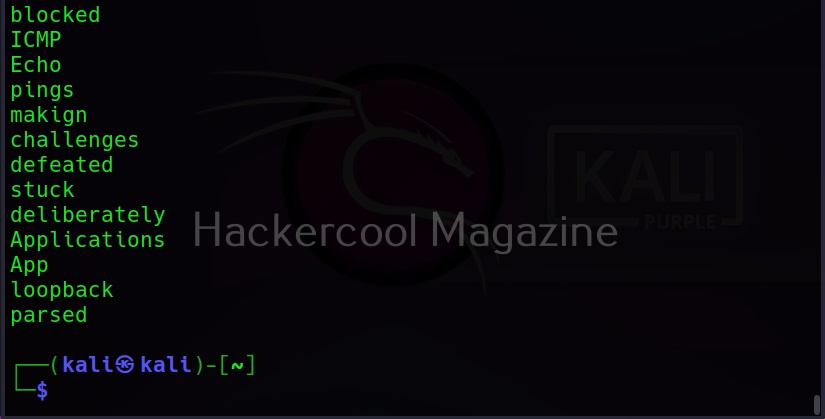

Then it will create the wordlist for you as shown below.

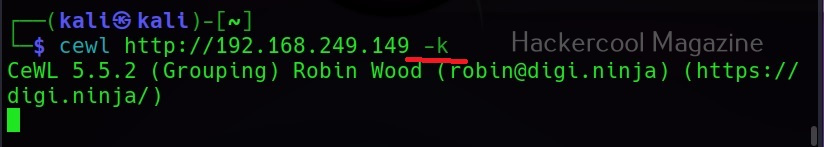

Keeping the downloaded file (-k)

Specifying the ‘-k’ option the downloaded file can be saved.

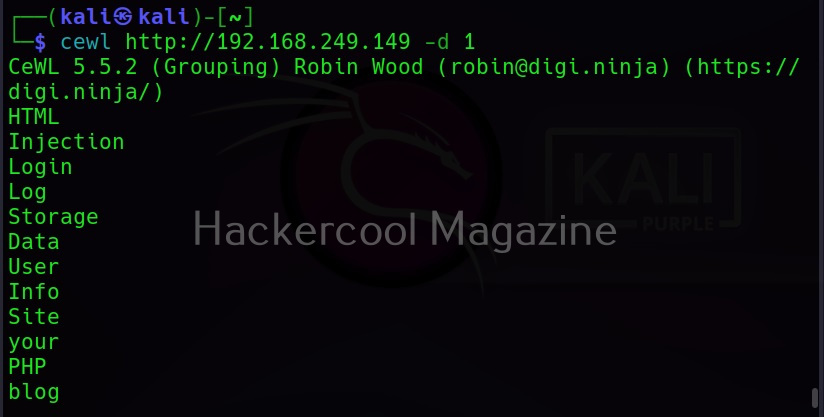

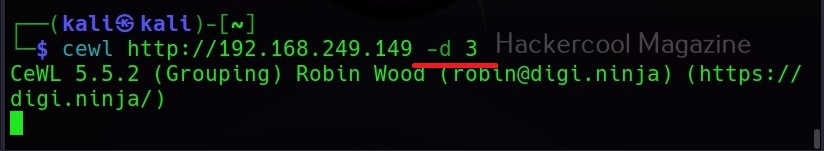

Depth of spidering (-d)

When you specify a target to Cewl, it spiders to the dept of 2 by default. You can change it using this option. For example, let’s set the depth to 1.

Or 3 may be.

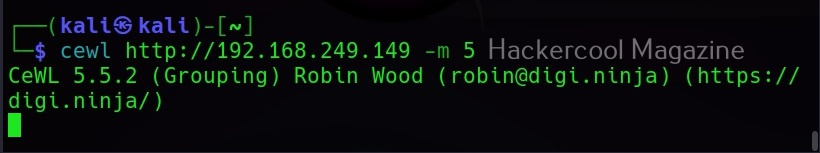

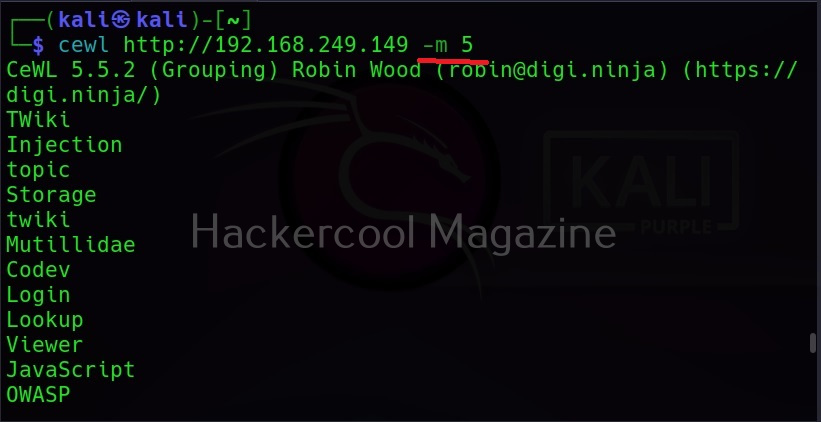

Minimum word length (-m)

This option can be used to set the minimum length of the passwords cewl creates. For example, nowadays, most services set the minimum length of the password to at least 5. So there’s no use creating passwords with length less than the minimum length your target has set, If you have noticed the above results, the default minimum length for cewl is 3. Let’s set it to 5 for example.

As you can see in the above image, there are no longer passwords of length less than 5.

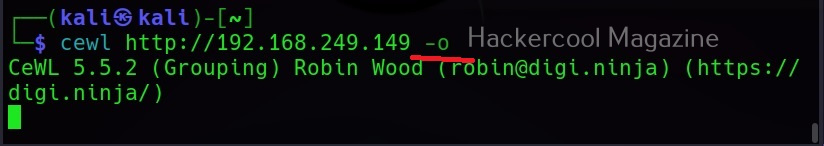

Spidering other sites (-o)

Setting this option allows cewl to spider another external sites during spidering of the target.

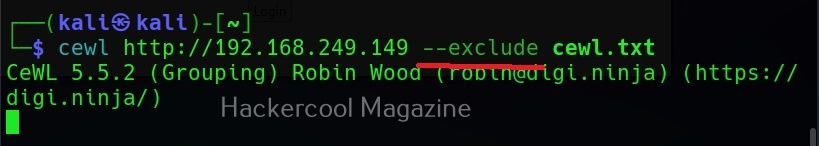

Don’t scan specified paths (–exclude)

If the target website is too large, you may want to skip some paths or maybe you just want to skip some paths as they may not have any passwords. You can use this option what cewl to exclude the paths you don’t want to scan. Then paths should be supplied in a file.

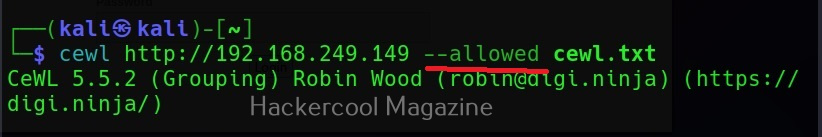

–allowed

This option is used to specify regex patterns of the path to be followed. If the pattern doesn’t match, it drops the scan.

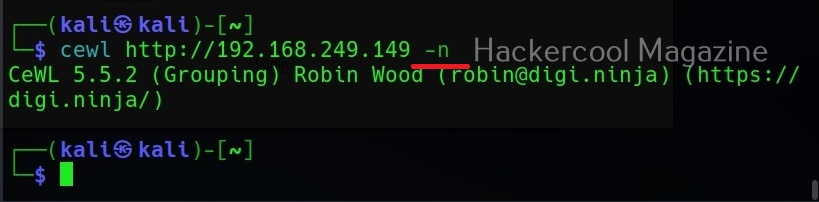

No wordlist please (-n)

If you don’t want the wordlist to be printed, you can use the “-n” option.

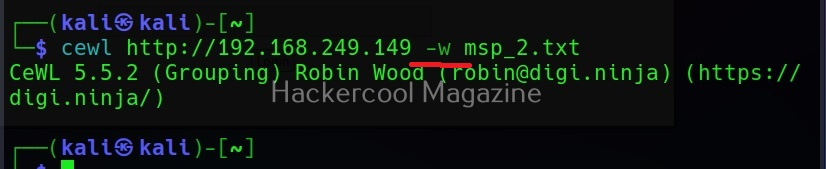

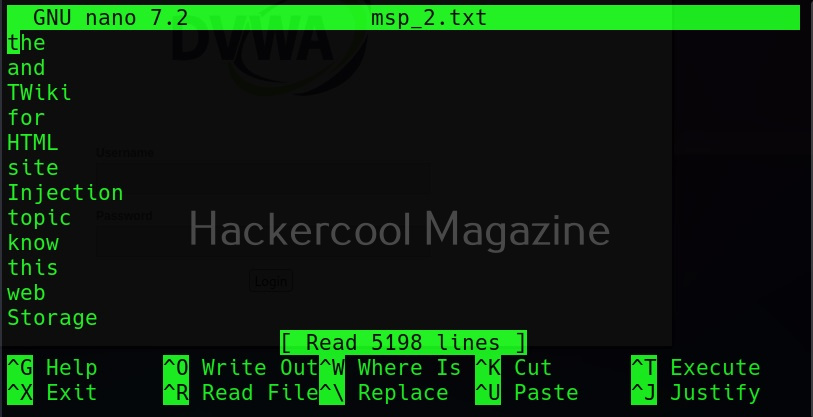

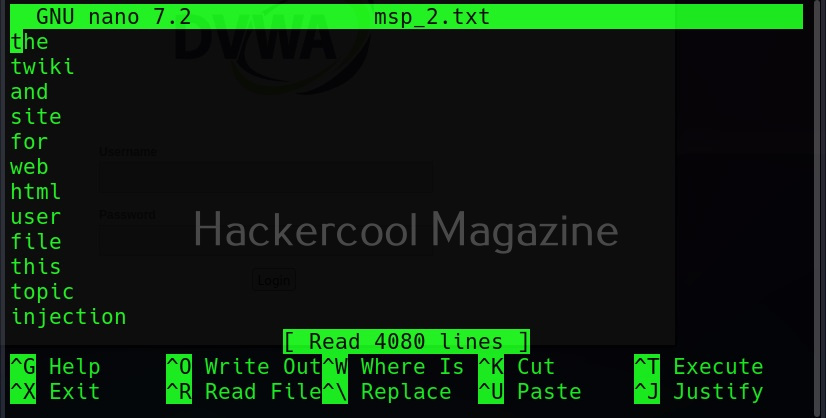

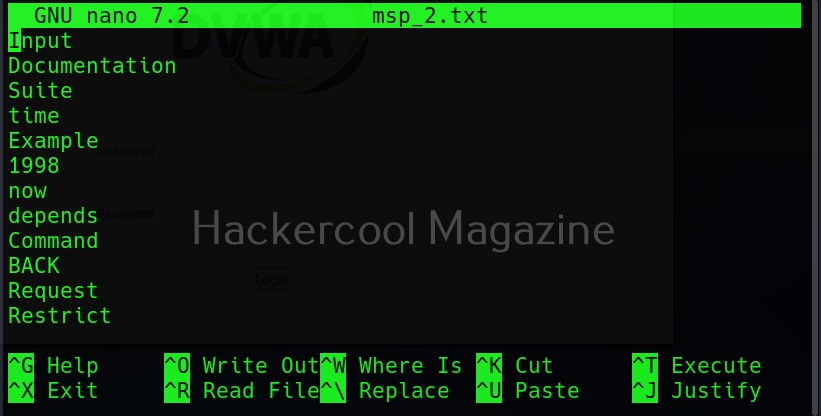

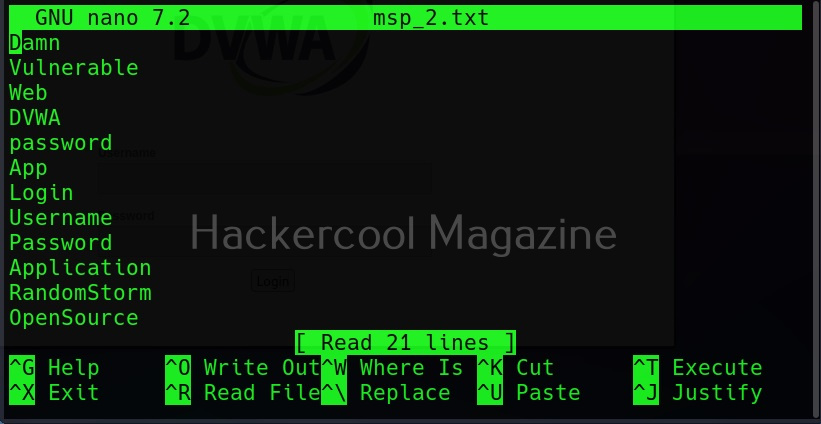

Saving the output (-w)

Till now, you have seen that Cewl has been printing the wordlists it creates to the terminal. The output can be copied and pasted in another file to be saved from using as a wordlist. But why take all this effort when we can just save the output to file, using the ‘-w’ option.

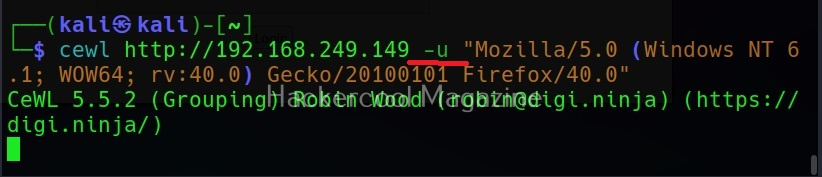

Use User agent (-u))

A user agent is a characteristic string that allows web server to identify the browser and operating system and we are using. You can see your user agent here. Using the (-u) option, cewl allows you to be get a specific user agent while spidering the website.

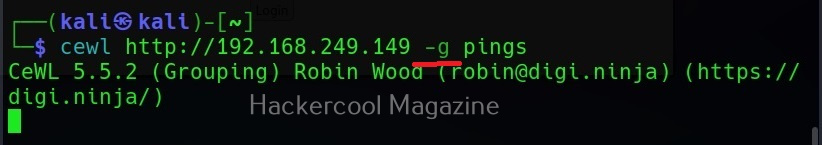

Groups of words (-g)

Setting this option allow cewl to return group of words along with single words.

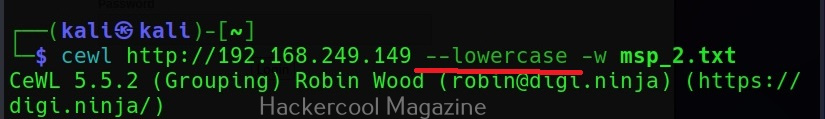

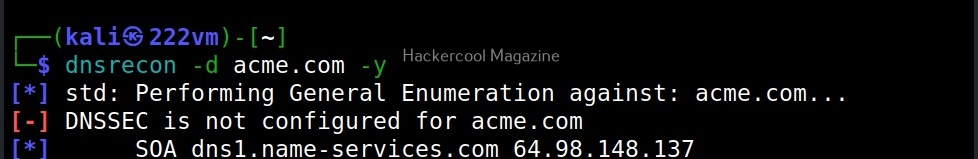

Turn all generated passwords to lowercase (–lowercase)

Setting this option allows us to 16 turn all the passwords cewl generates into lower case.

Here is the result.

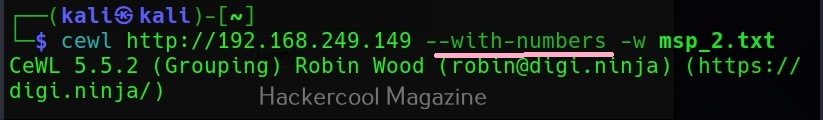

Include words with numbers too (–with-numbers)

While spidering, if cewl finds any words with numbers in them, it just ignores them. But many passwords contain numbers too. By setting this option, cewl collects numbers as well.

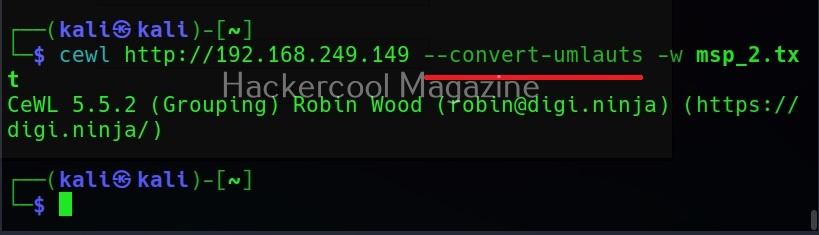

–convert-umlauts

Setting this option to while using cewl converts common ISO-8859-1 umlauts.

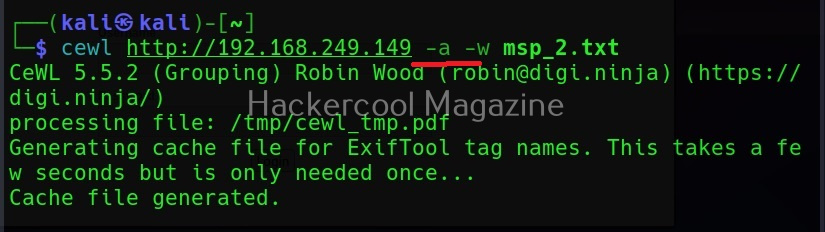

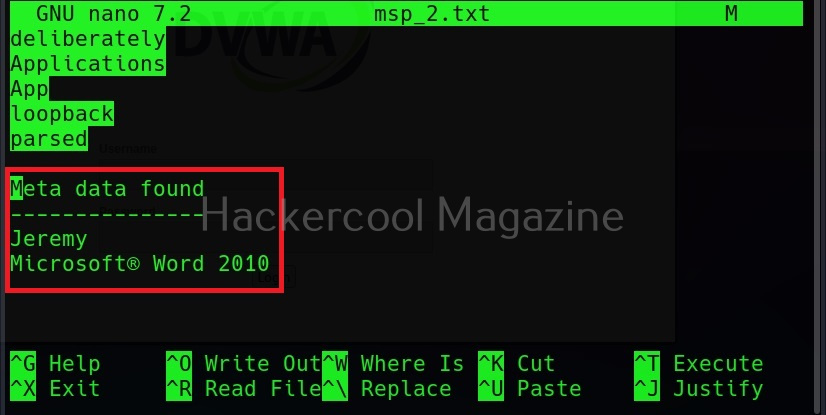

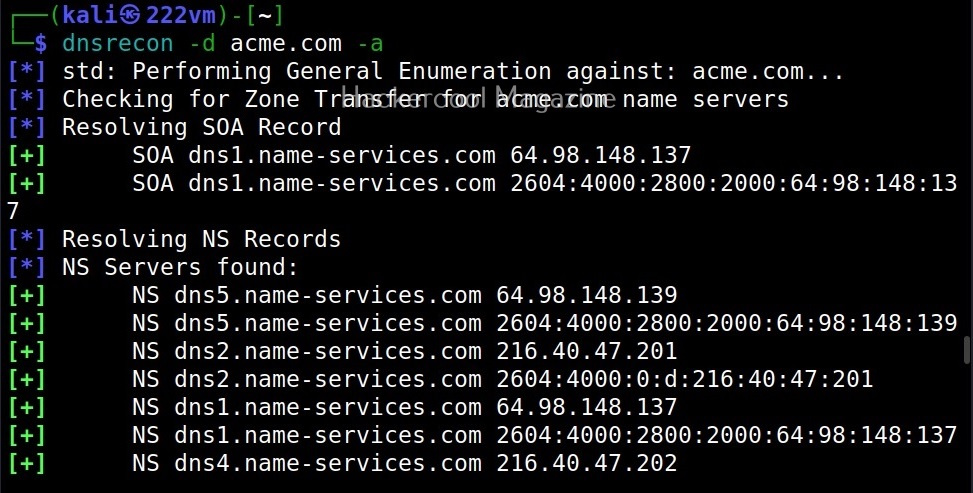

Include meta data too (-a)

When we set this option, Cewl includes metadata found while spidering the website apart from the words.

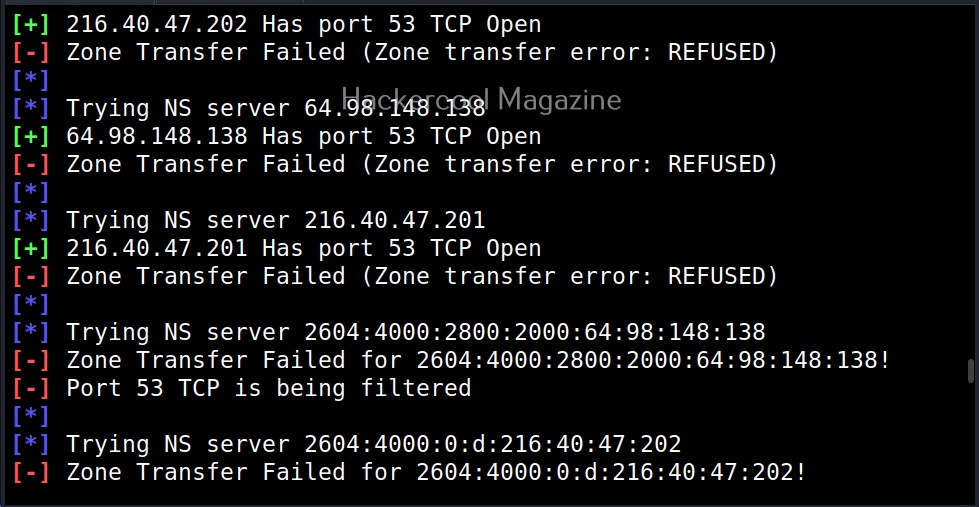

This metadata found is included at the end of the output files as shown below.

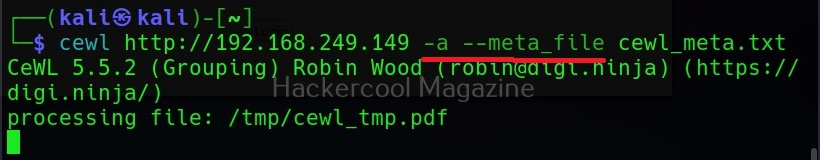

Save metadata found to a different file (–meta-file)

You can even save all the metadata found on the target site to a different file as shown below using the “–meta-file” option.

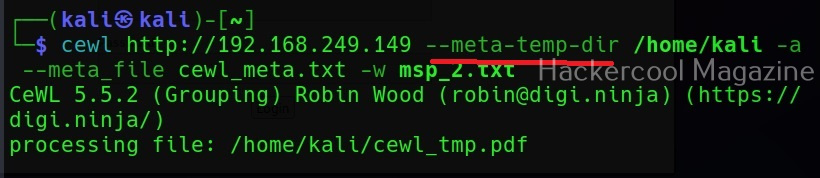

In the above image, you can see that cewl, while processing metadata creates a temporary file. This file known as cewl-temp.pdf is created in the /tmp directory by default. We can change the location of this file by using the “—meta-temp-dir” option as shown below.

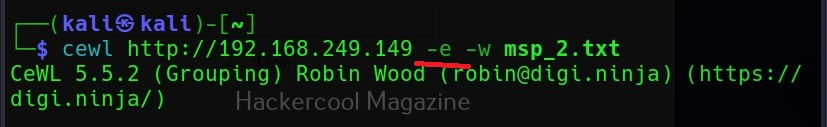

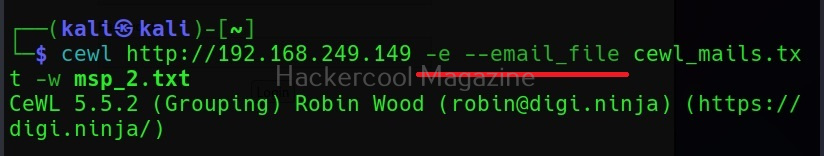

Gather emails too (-e)

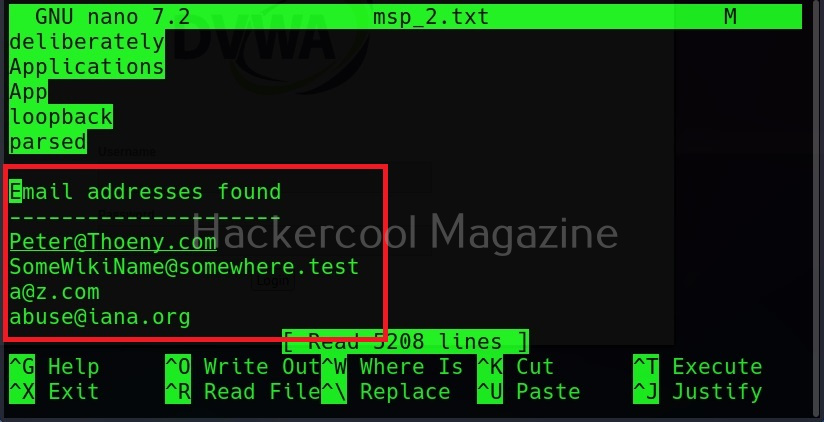

Not just metadata, you can even process emails using cewl with the ‘-e’ option.

Save collected emails in another file (–email-file)

These collected emails can also be saved in another file using the “–email-file” option.

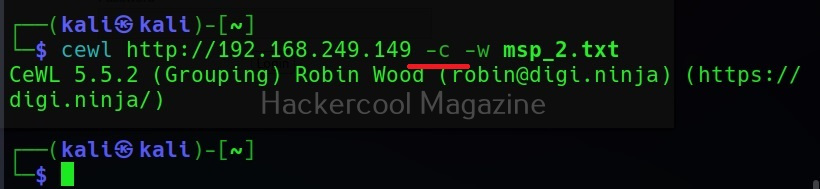

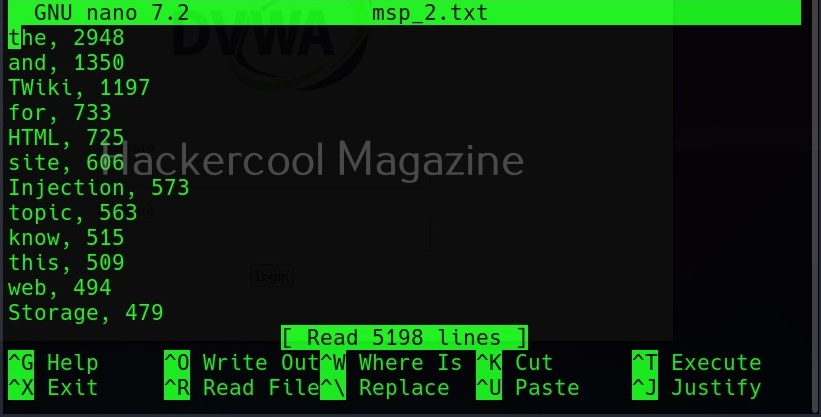

Show the count for each word (-c)

Setting this option shows the count for each word.

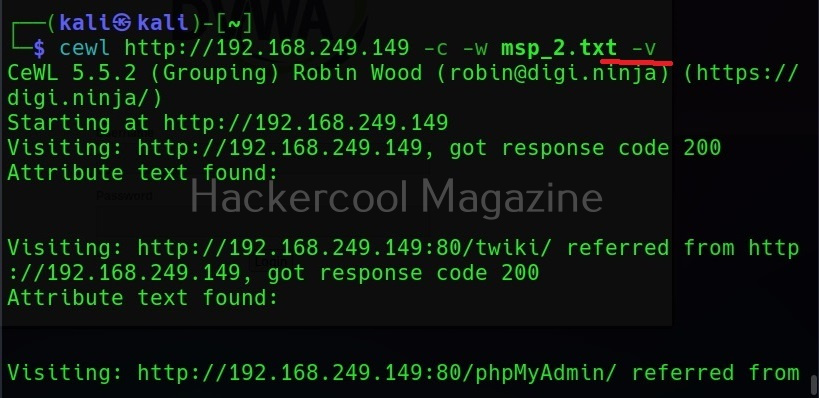

Verbose mode (-v)

Just like every other tool, this tool to has verbose mode that gives detailed information.

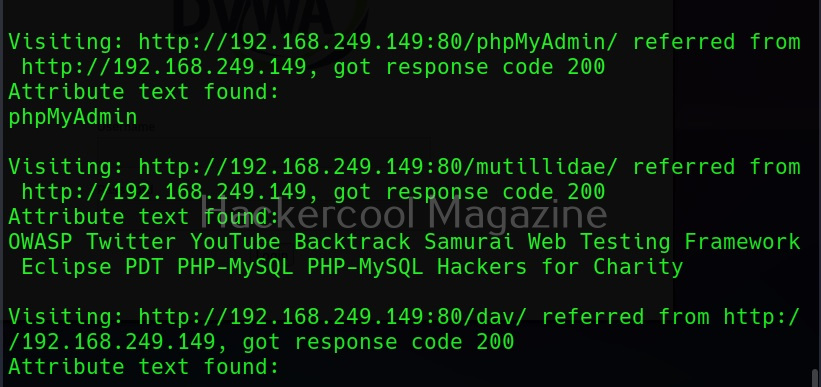

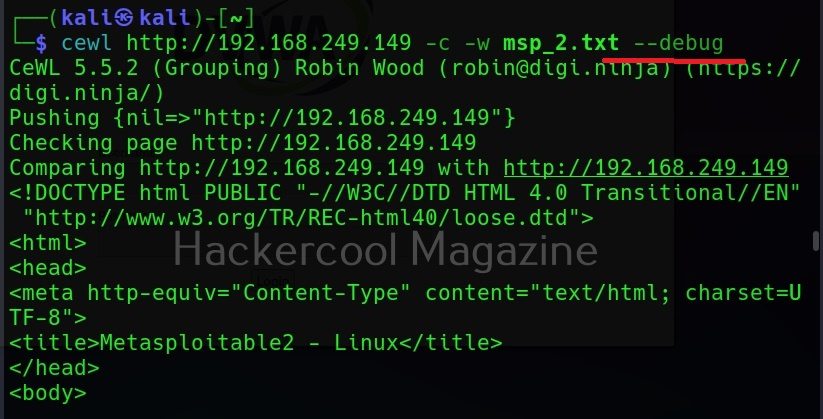

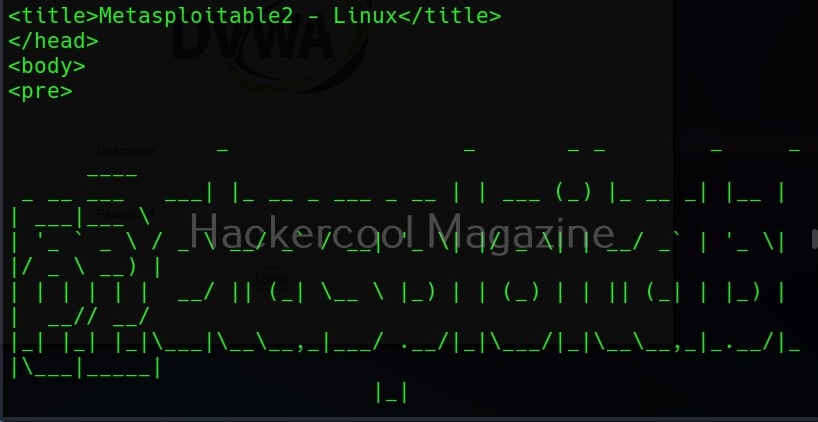

Debug mode (–debug)

Similarly, the “–debug” option gives detailed debugging information too.

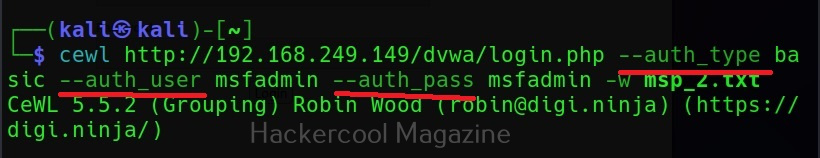

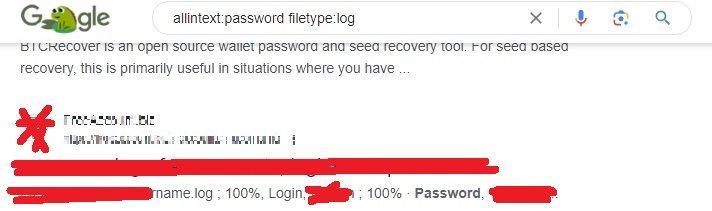

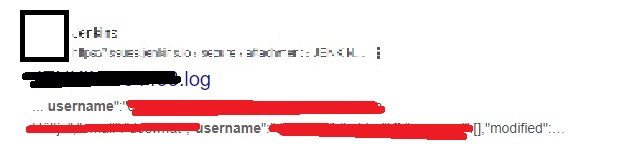

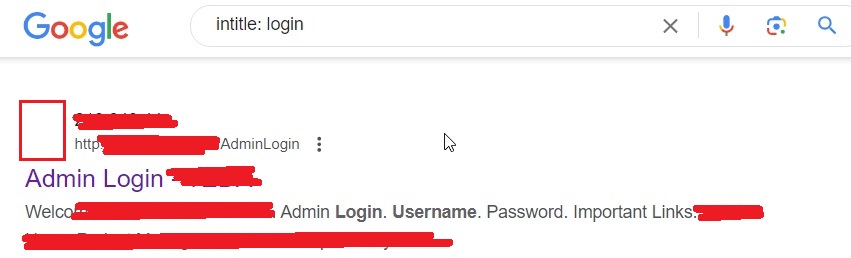

Authentication

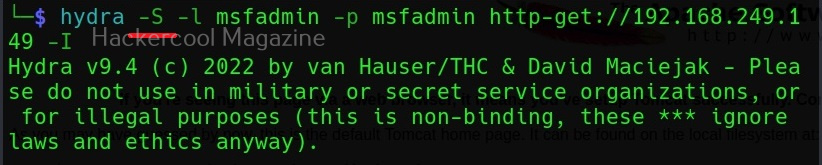

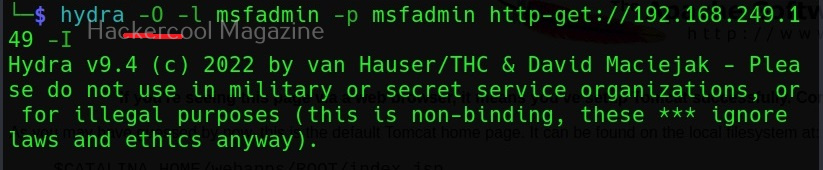

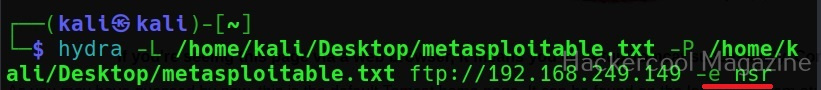

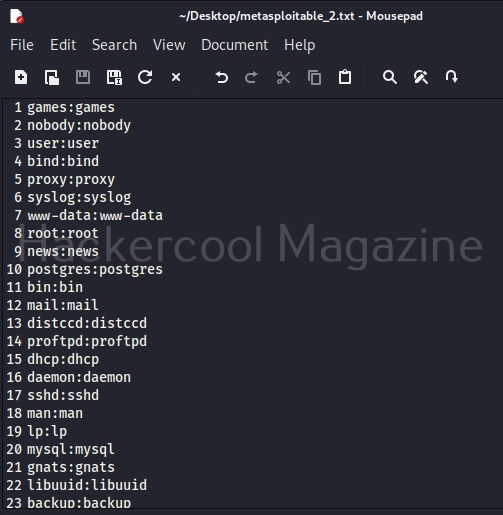

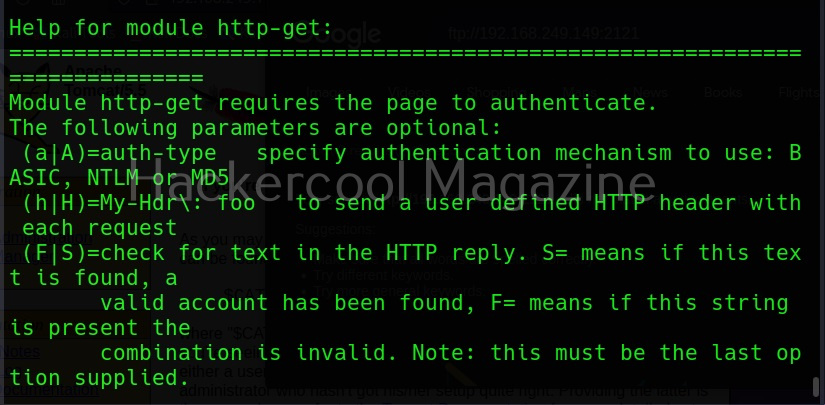

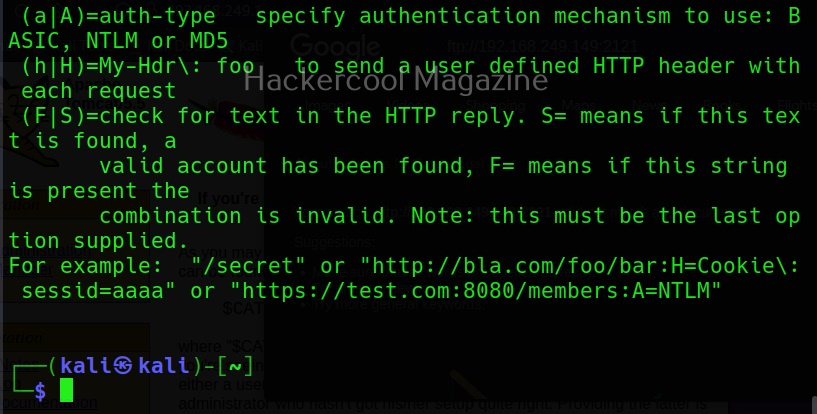

Some sites need authentication to spider it. Cewl allows authentication of websites too.

It supports both basic authentication and digest authentication. The “auth_type” option is used to set the type of authentication. The “–auth _user” and “–auth_pass” option can be used to set username and passwords respectively.

Here’s the output.

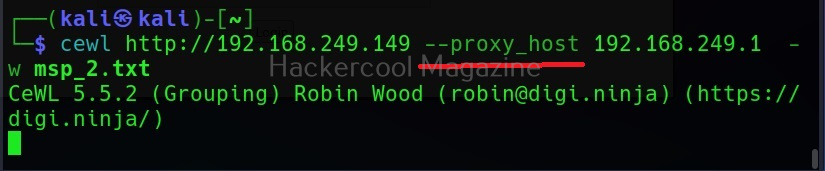

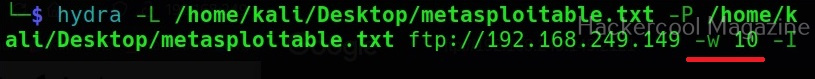

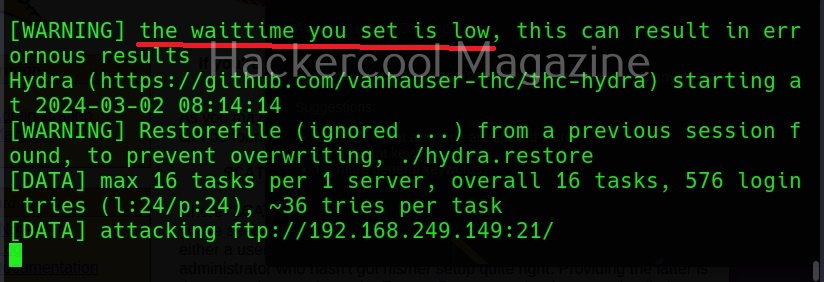

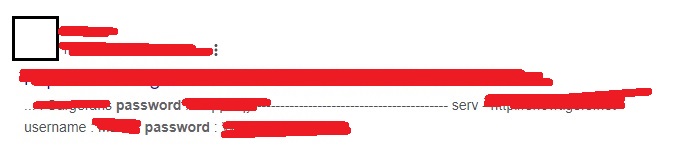

Spidering through proxy

Spidering, no matter what the purpose is very noisy. Cewl has an option to spider through a proxy using the “–proxy_host” option.

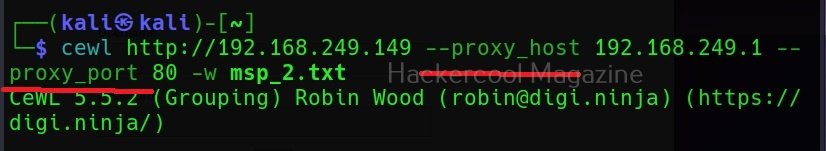

You can even specify the port of the proxy using the “–proxy-port” option.

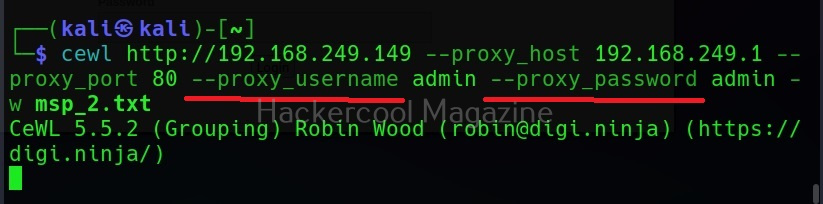

Cewl even has feature of authenticating to the proxy server using the “–proxy_username” and “–proxy_password” options.